In the summer of 2018 I stumbled across a random tweet by Marie Buhtz that shared a watercolor painting of a Cassowary — a colorful, stately bird from New Guinea.

I shared that tweet to the lovely tweeters that follow @h2ocolor there (now more than 6,800 lovely people) and simply said that we should all aspire to that level of mastery displayed in Matthew Cogswell’s stunning, detailed portrait.

That is why I’m very excited to finally share an interview I held with Cogswell over email these last few days. Since that initial tweet I’ve shared several of Cogswell’s pieces on Twitter. He’s nice enough to mention the gallery on Twitter every time he posts a new piece – making it very easy for me to be alerted when he published a new work.

You can see his work on his website. Perhaps before you read this interview you can hop over there and look through his work. I urge you to take your time. Open each piece and study them a little. His work is really very, very good and he also imbues meaning into each piece (as you’ll learn in the interview).

Now, onto the interview.

Thanks for taking a few moments to answer some questions. I’ve been a fan of your work since you posted the Cassowary on Twitter*. When did you begin with watercolor and what attracted you to the medium?

That’s so kind of you to say. It seems like so long ago that I did the Cassowary. I’ve been dabbling in watercolor since I was a child – mainly because it wasn’t messy and didn’t take ages to dry. I only started really focusing on animal art in the past couple years. I think what attracts me to the medium is its speed and clarity. You can get more luminous colors with watercolor than acrylic and can play around with the medium far more (IMHO) to get interesting effects like using salt or glazing or whatnot.

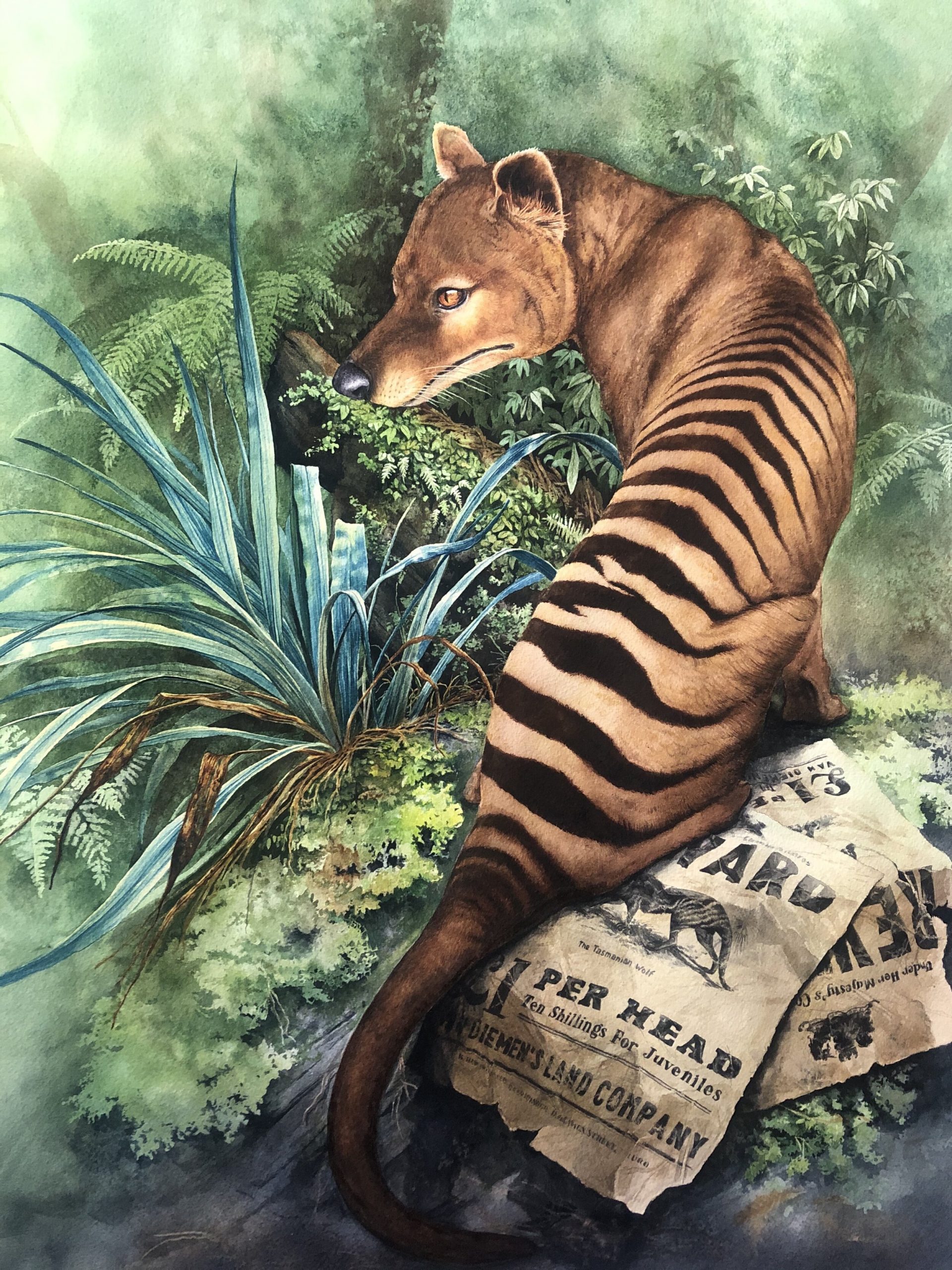

When I look at your artwork your composition immediately stands out. How the Cassowary is framed, the position and gaze of the Tasmanian Tiger, and even the hummingbird. How do you think about the composition of your work?

Since I paint from reference, a lot of composition gets dictated by the reference itself (I’m learning to break free of that constraint). I tend to like crescent or spiral compositions like the cassowary and Thylacine or zig-zags like the peacock or the tree I just painted. Things often start with the eye and spiral out but with so much going on the page people don’t get lost (and hopefully not bored)

I don’t really overthink the composition. I just do what feels right in the moment and move on. I just try to give their face enough room to not feel cramped and let things go from there.

Isn’t that called the Fibonacci sequence? Do you try to follow a pattern like that?

The fibonacci sequence is a specific KIND of spiral whose relation of expansion is set at a particular ratio. But you can have any kind of spiral. A bass clef is a spiral too, just a loose one. And that’s what the thylacine is mainly because that’s what the photo itself was, and then I built a rather triangular composition off of it. It’s all about where will you place the eye because if you get the eye right, you’re 80% there. Get it wrong, and it doesn’t matter how much else is right… the whole piece is ruined.

In your bio you have two phrases I’d like you to comment on. The first is that you say you “specialize in allegorical watercolors using symbolism of the natural worldâ€. Can you explain that a bit more?

“Allegorical watercolors using the symbolism of the natural world”. Most things tell at least a minor story to me unless they are a simple study. Some things like the Cassowary was about treating animals like we treat people; it’s lit and posed like a 18th century portrait (think “girl with the pearl earring”) whereas animals usually don’t get that kind of treatment. We light and pose humans in ways that we emotionally connect to, but animals are more direct and separated showing that we don’t emotionally connect to animals as much as we perhaps should and don’t show them the same courtesies. That told a story to me that could keep me interested long enough to paint it.

Other stories like “Nona Morta” (weaver birds) are more complex but essentially that one uses Village Weaver Birds, who are known for weaving hugely complex nests that often spill together in conglomerate nests taking over an entire tree. The birds are so numerous they destroy crops and their own world around them. I wanted to comment on how humans are inevitably the architects of our own demise. And my own political comment that all of them are looking to the left to save them since the right couldn’t give two shits about the environment. “Nona” and “Morta” were the roman fates who spun and cut the threads of life.

Quarantine (Irish Elk) was a slightly more personal story about how I’ve felt being in isolation: slogging through a seemingly endless wasteland feeling cold and alone. Each butterfly represents a friendship that died from atrophy, but that I still carry in my mind with a head to reconnect once we all emerge from our self imposed chrysalis. And there’s something dramatic and emo about identifying with an extinct species. At some point, there would’ve been the last one and how lonely would that have been? So, since I don’t want to come right out and say dramatic shit like that, I wrap it in symbolism. Being an artist is a constant struggle between wanting to be seen and wanting to hide.

You say that you utilize your bipolar disorder to your advantage. How so?

Yes, I have bipolar disorder rather badly. As I tell people – “It’s great half the time”. Though I am on medication for it, all that does is keep it from wrecking the lives around me. It is still there and I can still feel it. Much of my creative endeavors, from home renovation to painting start with a flurry of optimism until I get myself half way through and think “shit… how do I get myself out of this one?” And having to pull yourself out of something gives me enough energy and purpose to get out of bed and get something done. It’s a constant ebb and flow. I can use a mania to start something and then use the commitment I made to it (and not wanting to waste the hours I’d already put into it) to pull me through the depressions. For example, The Papyrus of Ani (the tree I just finished) too 1 week to paint half of it, and 3 weeks to paint the other half. I used the mania to get in there, and then the commitment to keep me going. I suppose in other ways I use it to my advantage is that it gives me melodramatic, histrionic feelings I can turn into at least marginally interesting and intriguing compositions.

Thank you for your candid responses Matthew.

What are your tools of choice? Favorites, least favorites? And how have your tools evolved since you started with watercolor?

I use primarily Windsor & Newton watercolors and only Arches cold press paper – often 300lb because it’s less likely to warp. No other paper comes close. I’ve tried Strathmore and such and despise it. It just can’t hold on to paint.

I use a lot of Neutral Tint. It’s great for building up rich blacks. And Watercolor dyes for intense color – like the blue of the cassowary.

As for brushes, I have a whole range of them from huge 3†flat, to Japanese brushes but I generally use very small brushes from 00-1. Sometimes as thin as 00000 which can paint the thickness of a human eyelash hair. Often I choose a small brush and over the course of the painting I’ll wear it out. I remember which brush was used for which painting and have considered framing it with the piece.

My tools haven’t really evolved much because I found something that works for me and stuck with it. I have been using watercolor mediums more and switched to a fountain pen for masking fluid. It’s more my techniques that have changed over the years. I took a 25 year break from watercolor painting and have only been doing what you see for a couple years. The red beta fish was the first one I did in nearly a lifetime.

It’s never too late to re-emerge I guess. Now I just need to find a gallery that will show my work. Easier said than done.

Do you have any artists that you follow these days? Who are your inspirations past or present?

OMG inspirations? SO MANY. I’m in love with the Hudson River School painters. 19th Century British watercolor like David Roberts, William Turner & John Constable. Nature artists like Edward Lear, and John James Audubon – and more contemporary ones like Raymond Harris Ching and of course the incomparable Walton Ford whom I idolize. Nowadays I spend more time on Instagram (@mattcogswellart – there’s lots of process shots there) than twitter but some artists I adore are:

@marcomazzoniart

@KathrynHansenDrawings

@Phil.Mumby_Art

@j.hunsung

@ZoeKellerArt

@LaurenMarxArt

@Takumi_Yokooka

@ArtNishimoto

@DebbieFriisPettitt

@TeagenWh

@ThierryDuvalAqua

Last question, what is next for your artwork? Are you working on anything in particular? A piece, a commission, a technique you’d like to learn?

I’m not working on anything big at the moment. There is a commission coming in and I’m saving space for that. But I am continuing my work on the Vanishing series of critically endangered birds – some of whom will be extinct by the time I finish the series.

Thanks so much for taking the time and coming up with such great questions.

END OF INTERVIEW

It was a real pleasure to interview Matthew and see that none of us are alone in our struggle to make our own art – it just so happens that his art is amazing and the struggle is invisible.

Thanks to him for taking the time to answer my questions. If you like his work, buy some on his website. You can follow him on Twitter.

* Editor’s note: Obviously Cogswell didn’t post the Cassowary on Twitter. I got that bit wrong. It wasn’t until I dug in and found the original tweet that I realized it was shared by someone else. He was nice enough not to correct me.